A few Thursdays back, I woke up around 4:30 a.m. to a bewildering Instagram DM.

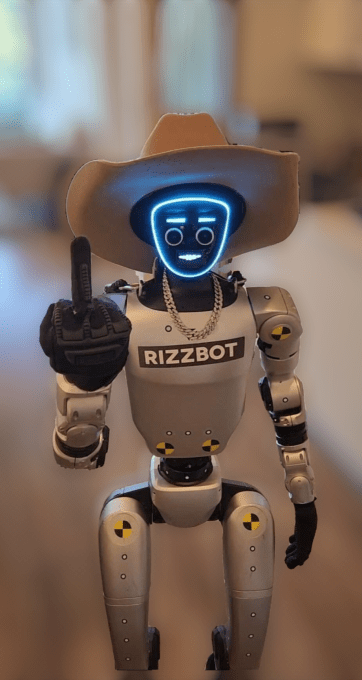

Rizzbot, a child-sized humanoid robot created by Unitree Robotics and boasting a substantial social media presence — over 1 million followers on TikTok and more than half a million on Instagram — had sent me an image: it was giving me the finger.

No text. No context. Just a robot with its middle finger extended.

While I was taken aback, a sinking feeling led me to suspect the reason. A couple of weeks prior, Rizzbot — or the individual behind its Instagram account — and I discussed a potential story. I found the account fascinating: a humanoid trotting around Austin sporting Nike dunks and a cowboy hat. It’s recognized for roasting, but also for flirting and havingfun. The term Rizz is derived from the Gen Z slang word rizz , which means charisma.

I was fascinated by the account’s increasing popularity. Humanoids usually make people uneasy. Concerns about privacy and job loss abound. Online, individuals hurl insults at them, most notably referring to them as “clankers.” Meanwhile, in the robotics community, experts are debating their optimal applications.

I viewed Rizzbot as a paradigm, helping others feel at ease in engaging with a humanoid.

Rizzbot consented to an interview, prompting me to reach out to experts to explore the future of humanoids as I prepared for the story. Two weeks after my first DM with Rizzbot, I informed it I would finally deliver interview questions on the ensuing Monday or Tuesday.

Techcrunch event

San Francisco

|

October 27-29, 2025

But life intervened, and I overlooked my own deadline. I was all set to send the questions first thing Thursday a.m., and I thought it was no big deal.

Too late. In the early hours of Wednesday night, Rizzbot dispatched that image. The message was clear: You broke your promise, so get lost.

I didn’t give up, though. I apologized to the robot (or its operator?) for the delay and assured I would send the questions right at the start of business hours. But when I attempted a few hours later, I was greeted with “user not found.”

The robot had blocked me.

Did I activate a fail-safe?

My friends found it hilarious that I was flipped off and blocked by Rizzbot, considering I had been talking excitedly about this story for weeks.

“LOL Rizzbot served you,” one friend texted me.

“YOU ARE FIGHTING WITH A ROBOT LOLOLOL,” another remarked. I attempted to reach out to Rizzbot on TikTok, a move one friend called desperate. But what choice did I have? I had pitched the story to my editor, invested hours in research, and — despite this conflict — Rizzbot would still be an intriguing subject for TechCrunch’s tech-savvy audience.

While my friends were laughing, I spiraled into a state of despair. Not only was my story effectively dead, but I had also become the girl who got blocked by a dancing robot.

My colleague Amanda Silberling volunteered to assist me. She reached out to the Rizzbot account to inquire why I was blocked. Rizzbot provided a terse reply: “Rizzbot blocks like he rizzes — smooth, confident, and with no regrets.” It subsequently sent her the same middle finger image it sent me. I thought: Wow, I wasn’t even unique enough for a different gesture of discontent.

Then, one friend presented a chilling perspective I hadn’t even considered. “It wasn’t a human reaction. I’m concerned for you.” It appeared I had inadvertently created my first robotic adversary, and the AI uprising had only just commenced.

Or had I? Was I truly fighting with a human?

I discovered that Rizzbot’s true name is actually Jake the Robot.

Its owner is an unidentifiable YouTuber and biochemist, as per reports. The robot itself is a generic Unitree G1 Model — manufactured in Hangzhou, China — and anyone can acquire one for $16,000 to over $70,000.

Rizzbot was trained by Kyle Morgenstein, a PhD candidate at the UT Austin robotics lab. He collaborated with a team for about three weeks, teaching the robot to dance and maneuver its limbs. Although much of the robot’s actions are preprogrammed, it is run via remote control, with its actual owner — apparently not Morgenstein — nearby to direct it.

If I had to speculate about the technology powering the robot — informed by discussions with Malte F. Jung, an associate professor at Cornell University who studies information sciences — it seems someone activates the robot’s actions, captures an image of whoever is engaging with the robot, processes it through ChatGPT or a similar language model, and then utilizes a text-to-speech feature to roast or flirt with the individual.

“The robot inverts the narrative of people mistreating robots,” Jung stated. “Now the robot gets to mistreat people. The real product is the performance.”

Morgenstein shared with other outlets that the actual owner of Rizzbot just enjoys entertaining people and showcasing the delight that humanoids can provide.

It remains unclear who manages the Rizzbot social media accounts, although when Rizzbot sent that image to Silberling, it also dispatched an error message — probably an accident — indicating it was out of GPU memory. This message suggested that an AI agent likely runs that account and may be auto-generating DM responses. It also implied that Rizzbot has only 48GB of memory.

“What makes you so sure it was ever a human?” my coder friend queried about the manager of the Instagram account.

In this AI era, anyone capable of training a robot probably possesses the skills to link an LLM to Instagram DMs. My blocking might have even been a fail-safe, my coder friend suggested, meaning I inadvertently triggered it myself by DM’ing in the early hours — even if it was a response.

However, there are indications that a person is in charge of Rizzbot’s social media: initial typos appeared in its first DM reply to me when I initially sought an interview.

Even so, unless Rizzbot discloses whether his social media manager is another bot (which seems unlikely in light of our dispute), I will probably never find out. Perhaps it doesn’t matter.

“If they invested $50,000 in a bot and a couple thousand for a 48GB memory machine, I wouldn’t dismiss anything,” my coder friend pointed out. “They’re clearly committed to the performance.”

It’s still robot brain fog

Rizzbot’s TikTok page alone has garnered over 45 million views. One clip features Rizzbot pursuing individuals on the streets, while another shows it colliding with a pole and tumbling into the street. A viral clip, presumably modified by AI, depicts Rizzbot being run over by a vehicle.

“Honestly, it seems amusing,” one founder friend told me, labeling the viral clips “robot brain fog.” He asserted that the AI is basic, but the robot’s concept is a “humorous fusion” of internet absurdist humor and the lightness that much of social media lacks nowadays. “It interacts with people in a unique manner.”

My Rizzbot exploration continued to provoke thoughts about the place of humanoids in our culture. Every sci-fi film I’ve ever viewed — from “Blade Runner” to “I, Robot” overwhelmed my memory. How concerned should I be now that I’ve created my first humanoid enemy?

“Performance truly appears to be the main application for these kinds of robots,” Jung shared, indicating that Rizzbot resembles “a contemporary take on street performance with a hand puppet.”

“Often, hand puppets have a sarcastic edge,” he added.

Apart from Rizzbot, he cited the Spring Festival performances in China, where humanoids dance alongside humans, while in San Francisco, spectators visit the boxing arena to watch robots throw punches.

“Robots will evolve into primary mass entertainment figures, including performers, dancers, singers, comedians, and companions,” Dima Gazda, the founder of the robotics company Esper Bionics, remarked, noting that humans will transition to niche, top-tier talent. “As robots acquire grace and emotional insight, they’ll blend into performances and interactive experiences more seamlessly than humans.”

Fortunately, at this moment, dancing robots seem challenging to scale en masse, according to Jen Apicella, executive director at the Pittsburgh Robotics Network. Therefore, I don’t have to dread the escalation of this conflict to, for example, an army of dancing, rizzing robots personally arriving at my door. Not that such a thought crossed my mind.

It has been over a week since I was blocked, and I find myself reflecting on the joy I experienced watching Rizzbot pursue people on the streets. My favorite video featured a woman dancing on Rizzbot. A crowd gathered around the spectacle; people appeared genuinely entertained, perhaps eager for their own chance to dance on a robot.

I always joked with my friends about wanting to keep robots on my good side in case a revolution occurred. But as I wrote this article, I found myself almost embroiled in another AI conflict — this time with Meta AI, which I had never engaged before. I accidentally initiated a conversation with Meta AI while searching for my old chats with Rizzbot on Instagram.

Meta’s bot responded, “Yoo, what’s good fam? You referring to me as Rizzbot? 🤣 What’s going on?”

I decided it was time to log off.